My clip of runners descending the famous “Chimney” at the 2018 Kilnsey Show:

My clip of runners descending the famous “Chimney” at the 2018 Kilnsey Show:

Sounds like it should be a pub, but more prosaically it’s a couple of midweek fell races in the Lake District I’ve done recently. Here are a few top tips should you wish to give either or both of these a crack sometime in the future.

Hot off the press – or more fittingly, while legs are still aching – was last night’s Blisco Dash, from the Old Dungeon Ghyll to the summit of Pike o’ Blisco via Redacre Gill and back. Dash for some maybe, but for me 2000ft of unremitting – and walked – climb, followed by 2000ft of braked and thigh-sapping descent. So much so that the flat half mile of road at the end was the toughest stretch of all, as limbs threatened to cease basic functioning with the finish line in sight. “Good running form” went out the window as I pretty much waddled the run in, and was grateful those around me seemed similarly affected as at least I didn’t lose any places.

But it was great to take part in this classic Lakes “AS” on another glorious Lake District summer evening. It’s pretty special being up there when the setting sun displays the fells at their best.

Just to note that the line off the summit is to the right of the way up (to avoid meeting those scrambling up the summit rocks head on). And that there really are precious few opportunities for the lactic acid to flush out on either the climb or descent. It’s certainly not one for the first-time fellrunner – you need to have a few thousand feet in the bank before giving it a go.

Just to note that the line off the summit is to the right of the way up (to avoid meeting those scrambling up the summit rocks head on). And that there really are precious few opportunities for the lactic acid to flush out on either the climb or descent. It’s certainly not one for the first-time fellrunner – you need to have a few thousand feet in the bank before giving it a go.

Whereas, the Reston Scar Scamper is perhaps a race with a broader appeal, for lots of good reasons. You register at the Hawkshead Brewery for a start (which confusingly is in Staveley, 10 miles from Hawkshead). There’s only 1000ft of climbing in the 3.5 miles, divided into 2 climbs, allowing a bit of “recovery” in between. And the River Kent flows past the finish line – very pleasant for a post-race cool off.

It was nice to get to know a bit of the Lake District that I must have zoomed past dozens of times before without really noticing. Reston Scar is on your right just after Staveley on the main A591 to Windermere. All eyes are normally on the first sight of the lake and the famous fells beyond, but there is much merit in these foothills and of course in the loftier fells around Kentmere to the north. Nice to have your perceptions challenged from time to time.  Anyway, fingers crossed both of these races have been good preparation what I’ve got in mind next – the short races at Ambleside, Burnsall and Grasmere shows respectively. Hope to see a few Striders at some of these over the next few weeks.

Anyway, fingers crossed both of these races have been good preparation what I’ve got in mind next – the short races at Ambleside, Burnsall and Grasmere shows respectively. Hope to see a few Striders at some of these over the next few weeks.

You wait ages for one then two come along at once. Thought I’d share how my first 24 hours back with Valley Striders (after a 10 year interlude) have gone. Two fell races on successive evenings. I’ve given myself an evening off this running lark tonight quite happily!

On Wednesday I did the Otley Chevin race. This is a good introduction to fellrunning for us north Leeds types, being the nearest fell race to Leeds on the calendar and a relatively straightforward prospect – run to the top of the Chevin from Otley town centre and back. Of course, it’s still pretty demanding in its own way. Most of the 700ft climb comes steeply all at once and needs pacing carefully, otherwise you really suffer on those interminable steps (215 – count ’em). Once at the top, you’re very quickly into the rapid descent, so not much time to do the transition from uphill to downhill running (two very different disciplines). And the sting in the tail is the long, flattish run-in through the coach park and down the cobbles of Queens Terrace – difficult to do a flat-out finish along here.

Anyway, it all seemed to go pretty well and it was good to be back fellracing in a Striders vest for the first time since Withins Skyline 2007! Stiffness wasn’t too bad in the morning, which encouraged me to head up Wharfedale later in the day and have a crack at the Kettlewell Anniversary race as well. This presented a rather different kind of challenge, having 2 significant climbs and descents in its 5 miles, plus an abominably stony track towards the finish (almost like scree running at times). After the exertions of the previous evening, I was even more glad to reach the finish line than usual. However, this was more than compensated for by the spectacular scenery on a gorgeous Dales evening, plus the route being mainly on sheep-cropped grass, always a pleasure to run on. And the convivial, informal banter of the “50 folks in a field” doing their mildly eccentric midweek thing definitely takes the pressure off – no big race nerves here!

Due to working weekends at the moment, I’m on the lookout for midweek short fellraces like these this summer, and happy to offer a lift to any Striders that want to give one a go.

The initial climb of the Kettlewell Anniversary race up to Gate Cote Scar

I’m a bit of a fairweather fellrunner to be honest, preferring spring, summer & autumn races to the harsh stuff over the winter. If there’s one exception it’s the Stanbury Splash, a mid-January mini-adventure over the Haworth moors to and from Penistone Hill. 6 miles in total with plenty of exciting descents and 4 stream crossings – hence its name.

This year’s “Splash” on Sunday was the first of the “new era” of Penistone Hill races – the legendary Woodentops having now passed the baton on to Wharfedale Harriers – but it seemed a pretty seamless handover. As usual, I got there early, as delays with parking, registration and kit selection can happen. Note to self – in January, print out the universal race entry form and fill it in at home, rather than attempting to fill it in on the day with freezing cold hands! And predictably I changed my mind 3 times about what combination of kit I was taking, eventually plumping (rather cautiously, although it was very cold) for a lightweight breathable walking jacket. I found this worked well – I didn’t overheat during the race – and I wasn’t too put out that many had just opted for a running vest. A different breed!

At least with the Penistone Hill races you’re starting at the top of the hill, so you get a pretty good idea of what conditions will be like throughout the race. The flip side of this is that you often get a good descent towards the start of the race, and an agonising climb back up at the end. But it does provide a good spectacle, and the view from the Back Lane car park of 300 runners charging down the hill towards Sladen Beck is a memorable one – almost reminiscent of a medieval battle scene!

After that initial down and up you do a full loop of Ponden Kirk before repeating the first mile and a half in reverse on the return. Conditions were certainly kinder than last year, which was all freezing rain and swollen streams – this time the “splashes” were no barrier and I got round 10 minutes quicker than in 2017. The sight of the finish line on the cricket pitch – with the tea urn and pile of broken biscuits – always very welcome!

So many thanks to Wharfedale Harriers, the Woodentops, and to all the supporters on the day, including everyone that took photos and clips and generously shared them so we can relive it all again from the comfort of home. See you next January.

Just back from running today’s Burnsall Classic Fell Race – a brilliant event and the “classic” tag well-earned.

I’ve blogged before about Burnsall’s renowned history and records, but what stood out today for me were two things. Firstly, the particularly good atmosphere and friendly banter between runners before and after the race. I got chatting to a couple of lads while recce-ing the course beforehand who were only too willing to share their route-choosing tips and reminiscences of previous races. Eg, we decided that keeping to the left of the tree straight after the wall on the descent was the best bet – I think this was proved correct! Good to give the “lower” half of the race a proper recce on the day as strictly-speaking it’s out-of-bounds the rest of the year.

Secondly, loads of chat at the finish line about just how good a course it is, and I have to agree. It’s got a bit of everything squeezed into its 1.8 miles. The initial runnable climb, the steeper bit near the top where you have to walk, a proper wade through heather, the awkwardly steep (and today, slippery!) initial descent, the wall to hurdle and then the exhilarating rush down to the finish. And only 50 yards of road at the beginning and end (albeit with loads of spectators!). It’s like all the best bits of fellrunning neatly packaged into 20 or so minutes.

You can toy with a few tactics too, although probably more of an issue for better runners than me. I made a daft effort to get ahead of a few just before the wall on the climb – knowing the difficulty of overtaking from then on – and almost came to a complete stop straight after and lost all the places again! Further on, some near me on the descent tried their luck on the heather rather than the path – not sure it worked for them though.

So overall, great day, sure I’ll be back next year, and many thanks to all the organisers and volunteers that make it happen.

A day long circuit of the Lake District in the footsteps of Coleridge.

In a previous post I reflected on Samuel Taylor Coleridge’s account of his perilous descent from Scafell in 1802. The passage is widely-quoted as being the first recorded example of that now well-established genre of literature: non-fiction mountain adventure. Indeed, because the route he took (known as Broad Stand) is now graded a “Moderate” rock climb – and because climbs have to be recorded to be officially recognised – 1802 is often mentioned as being the Year Zero of the sport of climbing.

But the descent of Broad Stand was just one short incident in a much larger adventure. Coleridge was in the middle of a 9-day circular walking tour of the Lake District, starting from and finishing at his home in Keswick. Today, long walks are familiar to many, and a mainstay of the tourist industry in places like the Lakes. But in 1802, it was pretty much unheard-of to venture into the mountains for the sake of adventure alone. Coleridge was doing something highly unusual to head off on a hike like this, let alone almost fall down a mountain on the way.

Obviously, there is a fine line between adventure and foolhardiness, and Coleridge – without previous knowledge of Scafell, let alone map or compass – crossed it by descending Broad Stand. But his spirit of adventure in taking on the 9-day tour, in defiance of the conventions of the time, is still admirable. We all need a little bit of adventure now and then!

We know about Coleridge’s tour because his write-up of it, in the form of 2 letters and various notebook jottings, has survived. It’s available here and going through it, with a few OS maps alongside, it’s possible to plot the route he took all those years ago. An obvious thought follows – would it be possible to retrace this route, and perhaps get a better insight into what inspired his famous writings?

A little bit of research reveals it’s already been done. In 1989 local writer, the late Alan Hankinson, walked almost the entire route, and in 1991 his fine book Coleridge Walks the Fells was published. His walk was a very noble enterprise, in that it turns out that the vast majority of the route – mostly just tracks in 1802 – is now roads, and main roads at that. Hankinson reluctantly concluded that Coleridge’s spirit of adventure could not be recaptured by following his exact route on foot – and he said that nearly 30 years ago!

I had another day to me in the Lakes recently and decided to dedicate it somehow to Coleridge’s journey. In the end I settled on an acceptable compromise – a circular drive around the Lake District visiting various spots mentioned by Coleridge on his tour, plus a long journey on foot to where he went immediately after descending Broad Stand. Although this felt like trying to squeeze a 9-course meal into a lunchbox – and I’m not really in the business of recommending scenic drives! – it’s the best that could be done in 24 hours. A pretty full day as it turned out, but a rewarding one.

Coleridge started out from his home in Keswick – Greta Hall – just a couple of minutes walk from the town centre, but up on a hill and commanding a view that he raved about. It’s possible to walk up to the gates now and get a peep of this very fine residence and also the view of the mountains above today’s rooftops:

The route heads up the beautiful Newlands Valley, at the top of which is Moss Force, a disappointing spectacle on 1 August 1802 but a very fine one on 27 July 2017 after much heavy rain. Not often you can drive (and park!) so close to such a fine cataract:

Dropping down to Buttermere, Coleridge’s route took him over Floutern Pass, but for the modern day driver you have to go round Crummock Water and Loweswater. I pressed on along the main road to Egremont, missing the diversion Coleridge took to St Bees. An unsucessful addition to his journey this turned out:

Dropping down to Buttermere, Coleridge’s route took him over Floutern Pass, but for the modern day driver you have to go round Crummock Water and Loweswater. I pressed on along the main road to Egremont, missing the diversion Coleridge took to St Bees. An unsucessful addition to his journey this turned out:

I walked on to St. Bees, 3 miles from Egremont-when I came there could not get a Bed-at last got an apology for one, at a miserable Pot-house; slept or rather dozed in my Clothes-Breakfasted there-and went to the School & Church ruins-had read in the history of Cumbd. that there was an ‘excellent Library presented to the School by James Lowther,’ which proved to be some 30 odd Volumes of commentaries on the Scripture utterly worthless- & which with all my passion for ragged old Folios I should certainly make serviceable . . . for fire-lighting.

I continued on the main road to Gosforth, trying not to think about Sellafield looming to the right, and then up Eskdale to the foot of Hardknott Pass where I switched to fellrunning gear. Across the fields was Taw House Farm, where Coleridge spent the night after his Scafell exploits and where he wrote the letter describing them:

I had a choice of routes here – either to keep to Coleridge’s route from Scafell to Taw House on the west side of the River Esk, or to stick close to the east bank of the river and join up with Coleridge’s route 3 miles higher up. Either way, I knew it was most likely I would have to return the same way, as the river was in spate and probably unfordable. I decided on the latter route, to view some of the dale’s impressive rapids and pools:

I had a choice of routes here – either to keep to Coleridge’s route from Scafell to Taw House on the west side of the River Esk, or to stick close to the east bank of the river and join up with Coleridge’s route 3 miles higher up. Either way, I knew it was most likely I would have to return the same way, as the river was in spate and probably unfordable. I decided on the latter route, to view some of the dale’s impressive rapids and pools:

At the top, across the indeed-unfordable Esk, was the biggest fall of them all – Cam Spout – next to which Coleridge descended:

At the top, across the indeed-unfordable Esk, was the biggest fall of them all – Cam Spout – next to which Coleridge descended:

Having done so…..

Having done so…..

And now the Thunder-Storm was coming on, again & again!-Just at the bottom of the Hill I saw on before me in the Vale, lying just under the River on the side of a Hill, one, two, three, four Objects I could not distinguish whether Peat-hovels, or hovel-shaped Stones-I thought in my mind, that 3 of them would turn out to be stones-but that the fourth was certainly a Hovel. I went on toward them, crossing & recrossing the Becks & the River & found that they were all huge Stones…….

I came to a little village of Sheep-folds / there were 5 together / & the redding Stuff, & the Shears, & an old Pot, was in the Passage of the first of them. Here I found an imperfect Shelter from a Thunder-shower-accompanied with such Echoes! O God! what thoughts were mine! O how I wishes for Health & Strength that I might wander about for a Month together, in the stormiest month of the year, among these Places, so lonely & savage & full of sounds!

The stones are known as Sampson’s Stones, viewed here from the other side of the river with the sheepfolds to the left:

The low clouds were very suggestive of the weather Coleridge described. Indeed, the whole walk up the Esk was accompanied by the thundering sounds of falling water, which would have very much suited the author of “Kubla Khan” with its frequent references to water – sacred rivers, romantic chasms, mighty fountains and five miles meandering. Ceaseless turmoil seething indeed.

The low clouds were very suggestive of the weather Coleridge described. Indeed, the whole walk up the Esk was accompanied by the thundering sounds of falling water, which would have very much suited the author of “Kubla Khan” with its frequent references to water – sacred rivers, romantic chasms, mighty fountains and five miles meandering. Ceaseless turmoil seething indeed.

Returning to the car, I continued my own meanderings over Birker Fell and down to Ulpha Kirk in the Duddon Valley. Coleridge waxed lyrical about the place:

The Kirk standing on the low rough Hill up which the Road climbs, the fields level and high, beyond that; & then the different flights of mountains in the back ground, with wild ridges from the right & the left, running like Arms & confining the middle view to these level fields on high ground is eminently picturesque-A little step (50 or 60 yards) beyond the Bridge, you gain a compleatly different picture-the Houses & the Kirk forming more important parts, & the view bounded at once by a high wooded rock, shaped as an obtuse-triangle/or segments of a circle forming an angle at their point of junction, now compleat in a Mirror & equally delightful as a view/

Coleridge’s best friend in poetry, William Wordsworth, agreed about the area, so much so that a few years later he wrote a series of 34 sonnets dedicated to the River Duddon. Number 31 starts:

The Kirk of Ulpha to the pilgrim’s eye

Is welcome as a star, that doth present

Its shining forehead through the peaceful rent

Of a black cloud diffused o’er half the sky;

Happily, this particular pilgrim managed to take a photo just at the moment the sun shone on the shining forehead against a black cloud:

The Kirk seemed rather distinctive with its bells on the outside and (in that very civilised fashion) the door was open so you could have look around inside.

The Kirk seemed rather distinctive with its bells on the outside and (in that very civilised fashion) the door was open so you could have look around inside.

The next part of the drive – from Ulpha over to Broughton Mills – was very pleasant along a quiet, gated road. I soon came to The Blacksmith’s Arms where Coleridge:

Dined on Oatcake & Cheese, with a pint of Ale, & 2 glasses of Rum & water sweetened with preserved Gooseberries

I thought about going in and asking for the same but had second thoughts, particularly when the staff came out the front for a fag break. A lovely looking inn though:

My head used to feel a bit like that anvil after spending too much time in places like this back in the day….

My head used to feel a bit like that anvil after spending too much time in places like this back in the day….

Once you’re over the next hill into Torver the return to Keswick is a long way by main road, roads familiar to generations of visitors to the Lakes. I did stop off quickly at one famous spot well known to Coleridge – Dove Cottage in Grasmere, his mate Wordsworth’s place. But when Coleridge passed on this occasion he didn’t stop for long – William and his sister Dorothy were away, en route to France to visit Annette Vallon, with whom Wordsworth had had a child – Caroline – several years before, a fact known to Coleridge but not to the general public until the 1920s! This was August 9 1802 – 4 weeks later, and still on the road to France, Wordswoth wrote one of his most famous poems – “Composed upon Westminster Bridge, September 3, 1802”.

Well, that was a long day in the Lakes, but a memorable one. Obviously, you can only take so much in from behind the wheel, but I felt I got some sense of Coleridge’s tour from my journey, helped of course by the excursion into the wilds of Eskdale. Coleridge would have felt his circuit was taking him off into the unknown; to do that now you’d have to find a different circuit, off the roads. There is a well-known challenge called the Bob Graham Round – 42 peaks, again starting and finishing in Keswick. The “proper” fellrunning challenge is to do this in 24 hours – don’t worry, I’m not ready for that yet (ever) – but holiday companies also advertise it as a package walking holiday in manageable chunks. Maybe when I’ve got nine days to hand rather than one….

Well, that was a long day in the Lakes, but a memorable one. Obviously, you can only take so much in from behind the wheel, but I felt I got some sense of Coleridge’s tour from my journey, helped of course by the excursion into the wilds of Eskdale. Coleridge would have felt his circuit was taking him off into the unknown; to do that now you’d have to find a different circuit, off the roads. There is a well-known challenge called the Bob Graham Round – 42 peaks, again starting and finishing in Keswick. The “proper” fellrunning challenge is to do this in 24 hours – don’t worry, I’m not ready for that yet (ever) – but holiday companies also advertise it as a package walking holiday in manageable chunks. Maybe when I’ve got nine days to hand rather than one….

The following is often described as the first ever written description of a mountain walk. In this respect, the author was establishing a fine tradition: hot-headed Englishman storms up a mountain – gets into difficulty – escapes by a hair’s breath – lives to tell a great tale. It’s pretty flowery stuff in places, but still a classic account:

There is one sort of gambling, to which I am much addicted; and that not of the least criminal kind for a man who has children & a concern. It is this. When I find it convenient to descend from a mountain, I am too confident & too indolent to look round about & wind about ’till I find a track or other symptom of safety; but I wander on, & where it is first possible to descend, there I go-relying upon fortune for how far down this possibility will continue. So it was yesterday afternoon. I passed down from Broadcrag, skirted the Precipices, and found myself cut off from a most sublime Crag-summit, that seemed to rival Sca’ Fell Man in height, & to outdo it in fierceness. A Ridge of Hill lay low down, & divided this Crag (called Doe-crag) & Broad-crag-even as the Hyphen divides the words broad & crag. I determined to go thither; the first place I came to, that was not direct Rock, I slipped down, & went on for a while with tolerable ease-but now I came (it was midway down) to a smooth perpendicular Rock about 7 feet high-this was nothing-I put my hands on the Ledge, & dropped down / in a few yards came just such another / I dropped that too / and yet another, seemed not higher-I would not stand for a trifle / so I dropped that too / but the stretching of the muscle of my hands & arms, & the jolt of the Fall on my Feet, put my whole Limbs in a Tremble, and I paused, & looking down, saw that I had little else to encounter but a succession of these little Precipices-it was in truth a Path that in a very hard Rain is, no doubt, the channel of a most splendid Waterfall.

So I began to suspect that I ought not to go on / but then unfortunately tho’ I could with ease drop down a smooth Rock 7 feet high, I could not climb it / so go on I must / and on I went / the next 3 drops were not half a Foot, at least not a foot more than my own height / but every Drop increased the Palsy of my Limbs-I shook all over, Heaven knows without the least influence of Fear / and now I had only two more to drop down / to return was impossible-but of these two the first was tremendous / it was twice my own height, & the Ledge at the bottom was exceedingly narrow, that if I dropt down upon it I must of necessity have fallen backwards & of course killed myself. My Limbs were all in a tremble-I lay upon my Back to rest myself, & was beginning according to my Custom to laugh at myself for a Madman, when the sight of the Crags above me on each side, & the impestuous Clouds just over them, posting so luridly & so rapidly northward, overawed me / I lay in a state of almost prophetic Trance & Delight-& blessed God aloud, for the powers of Reason & of the Will, which remaining no Danger can overpower us! O God, I exclaimed aloud-how calm, how blessed am I now / I know not how to proceed, how to return / but if I am calm & fearless & confident / if this Reality were a Dream, if I were asleep, what agonies had I suffered! what screams!-When the Reason & the Will are away, what remain to us but Darkness & Dimness & a bewildering shame, and Pain that is utterly Lord over us, or fantastic Pleasure, that draws the Soul along swimming through the air in many shapes, even as a Flight of Starlings in a Wind.

– I arose, & looking down saw at the bottom a heap of Stones-which had fallen abroad-and rendered the narrow Ledge on which they had been piled, doubly dangerous / at the bottom of the third Rock that I dropt from, I met a dead Sheep quite rotten-This heap of Stones, I guessed, & have since found that I guessed aright, had been piled up by the Shepherd to enable him to climb up & free the poor creature whom he had observed to be crag-fast-but seeing nothing but rock over rock, he had desisted & gone for help-& in the mean time the poor creature had fallen down & killed itself.-As I was looking at these I glanced my eye to my left, & observed that the Rock was rent from top to bottom-I measured the breadth of the Rent, and found that there was no danger of my being wedged in / so I put my Knap-sack round to my side, & slipped down as between two walls, without any danger or difficulty-the next Drop brought me down on the Ridge…

The date of this escapade was 5 August 1802, and the author was the Romantic Poet (and wayward genius) Samuel Taylor Coleridge. Coleridge was on a 9-day walking tour of the Lake District and the extract is taken from his written account of it, a letter to his muse Sara Hutchinson (full text on the University of Lancaster website). The route he describes is now known as Broad Stand, which is the direct line between the two highest mountains in England – Scafell Pike and Scafell.

As befits a great writer, Coleridge could spin a good tale all right. What of course is missing from the story is how indeed he did get down to safety. The “out of body” stuff towards the end of para 2 suggests strongly of divine intervention – well, I suppose you could get away with that as an explanation in 1802. But he must have got down somehow. Perhaps he exaggerated the danger, a bit of poetic licence?, but all the guidebooks these days tell walkers to avoid Broad Stand like the plague – it should be the preserve of rock climbers only. How best to find out?

Take a look, of course. Fortunately, it’s possible to visit Broad Stand safely without putting yourself through Coleridge’s perilous descent, and that’s by looking up at it from the ridge at the bottom (known as Mickledore). I recently ticked a big one off the bucket list and climbed Scafell Pike for the first time, so went via the steep pass to Mickledore to look at Broad Stand on the way. Here it is: The sheep on the grassy platform in the middle of the photo gives some idea of scale. Coleridge’s route would have started around here and gone diagonally down to the left, down the numerous ledges he describes, finishing at the visible vertical split in the rock mentioned at the end of his account.

The sheep on the grassy platform in the middle of the photo gives some idea of scale. Coleridge’s route would have started around here and gone diagonally down to the left, down the numerous ledges he describes, finishing at the visible vertical split in the rock mentioned at the end of his account.

Put simply, the guidebooks are right. A solo climb up Broad Stand would be foolhardy at the very least – the whole scene is overpowering and I wasn’t tempted to go anywhere near the rocks. A descent – like Coleridge’s – would be a positive invitation to disaster. Note how the ridge itself falls away steeply to the left – any fall from Broad Stand would have you come to rest several hundred feet below.

The answer for lovers of Romantic Poetry was clear to me. Coleridge – only 29 at the time (he lived to 61) got away with it – to use his own words – simply by relying on fortune.

Fellrunning’s enduring legend – the most famous and extraordinary individual performance in the history of the sport – is Ernest Dalzell’s descent in the Burnsall Fell Race of 1910. 2 minutes 42 seconds of tumbling, whirlwind descent from the top of Burnsall Fell to the finish line in the village. In the 107 years since, no one else has got within a minute of it (see previous blog)*.

Of course, the scale of the record just fuels the legend, as many have doubted the time. How can we trust a handful of eyewitness accounts from so long ago? I’ve been a bit of a doubter myself – my own best descent time in the race is about 6 minutes – flat out. How could it be humanly possible to run a mile, 800ft downhill, in 2.42?

I had this question in mind whilst out on the course earlier this week. Standing by the summit cairn, the village seems just a speck far below, almost as if it would take at least 2.42 to paraglide down, let alone run. Jogging down, there’s only really one route – along a thin, steep path through the thick heather: (photo of last year’s race from woodentops.org.uk)

If the heather and gradient don’t slow you down enough, the path is worn down to the bedrock, and it’s this combination of steepness, heather and rock that makes progress so painfully slow, and Dalzell’s record seem so improbable.

But crucially, on the day of Dalzell’s record in 1910, the heather had been burned. His race, unusually, took place in September – almost all subsequent races have taken place in August with the heather still thick on the ground.

Further down the fell, just off the main path, I noticed an area where the heather was absent. I had a crack at running down this bit and it was a doddle – springy peaty turf and any rocks clearly visible and easily avoided. I reckon I was two or three times quicker here than on the path. Suddenly, it became a lot easier to envisage Dalzell throwing himself down a bare slope like this with abandon, just picking himself up from various somersaults and carrying on.

I was reminded of a few clips I’ve seen on youtube of that quaint English tradition of cheese rolling. In this annual event, competitors pursue a rolling cheese down Cooper’s Hill just outside Gloucester, a 200 yard-long grassy slope of 1 in 2 – a similar steepness to Burnsall. The fastest pursuers have perfected a technique of propelling themselves downwards by not just running but lying on their backs, rolling, diving forwards – whatever really! – and complete the course in seconds. Dalzell could well have used similar techniques on the bare slopes of Burnsall in 1910.

So, I came away from Burnsall the other day firmly convinced that Dalzell’s descent time was indeed possible, and that it will only ever be beaten if the Duke of Devonshire can one year conveniently burn his heather in time for Burnsall Sports Day.

Looking forward, as ever, to this year’s race on 19 August – you can enter online now

* and Dalzell’s overall time of 12.59 was only broken in 1977.

“This upside-down, inside-out version of running where the streets and roads are just passing distractions in a search for those places where the running is dirty and uneven, where the world’s natural disorder sparkles and rushes, bends and cracks. Running without blinkers on”.

One of my New Year Resolutions this year was to enter the Leeds Half-Marathon. So back in early Jan I filled in the entry form, paid my £34 (!) and the clock is now ticking to May the 14th.

Not that I’m a massive fan of road running, particularly not 13 miles of it. I did some 10ks a few years ago, but generally I prefer to get off the roads and onto the trails and hills. So why the Resolution?

We live pretty much on the Half-Marathon route, and on every second Sunday in May the road is closed for a couple of hours in the morning. So it’s always seemed rather churlish not to stand on the pavement, witness the spectacle of 10,000 people going past and give encouragement. I’ve done this for many years now and each year I’ve felt a bit more like participating, rather than just spectating. Finally, this year, it was time to give it a go.

It was only after entering that I actually began thinking about what preparing for and running a half-marathon entailed. Conventionally, several weeks of running on the roads in advance. And then the big day itself – 2 hours of plod, plod, plod along the streets (and that’s presuming all goes well). The prospect wasn’t exactly grabbing me.

It was only after entering that I actually began thinking about what preparing for and running a half-marathon entailed. Conventionally, several weeks of running on the roads in advance. And then the big day itself – 2 hours of plod, plod, plod along the streets (and that’s presuming all goes well). The prospect wasn’t exactly grabbing me.

But I’m glad to say I’ve rediscovered my enthusiasm. For this I have a couple of books to thank (and Leeds Libraries for having them in stock!) – both similarly-titled and on a similar theme: Running Free by Richard Askwith and Run Wild by Boff Whalley.

The key message of both books is simply that running should, more than anything else, be about fun and adventure. Not about watching the clock, shaving seconds off your PB or about doing something you somehow feel you should be doing. Rather, it should just be about enjoyment, the sheer pleasure that comes from getting out there and running about, much as we did as kids.

So, I’m now seeing preparing for the Half-Marathon as an opportunity to return to the kind of running I like doing best – off-road, up and down, through woods, fields, mud and streams. Fortunately, we have a natural playground on our doorstep in Meanwood – the Meanwood Valley – and I’ve been making the most of what the valley has to offer.

Actually, just recently, it’s been a whole lot of mud, particularly the stretch north of the ring road through Adel Woods. It’s been great not to be put off by the cut-up paths and puddles, if anything to seek them out. In fact, winter muddy running feels like yet another great discovery about the Meanwood Valley. Good job I’ve got an outside tap at home though!

So do take a read of the books if you can. The quote at the top is taken from Ch.31 of Boff’s book, describing a run he took up Meanwood Valley in 1986. I’m glad to say it’s still like that now.

As to 14 May itself, fingers crossed the preparation will allow me to enjoy it the best I can. But already I’ve got a feeling it’s going to be both my first and last half-marathon.

I was asked the other day why I thought the Meanwood Valley was so special. As I’ve spent much of 2016 trying to help protect one particularly valuable corner of the Valley, I thought this was a pretty timely question.

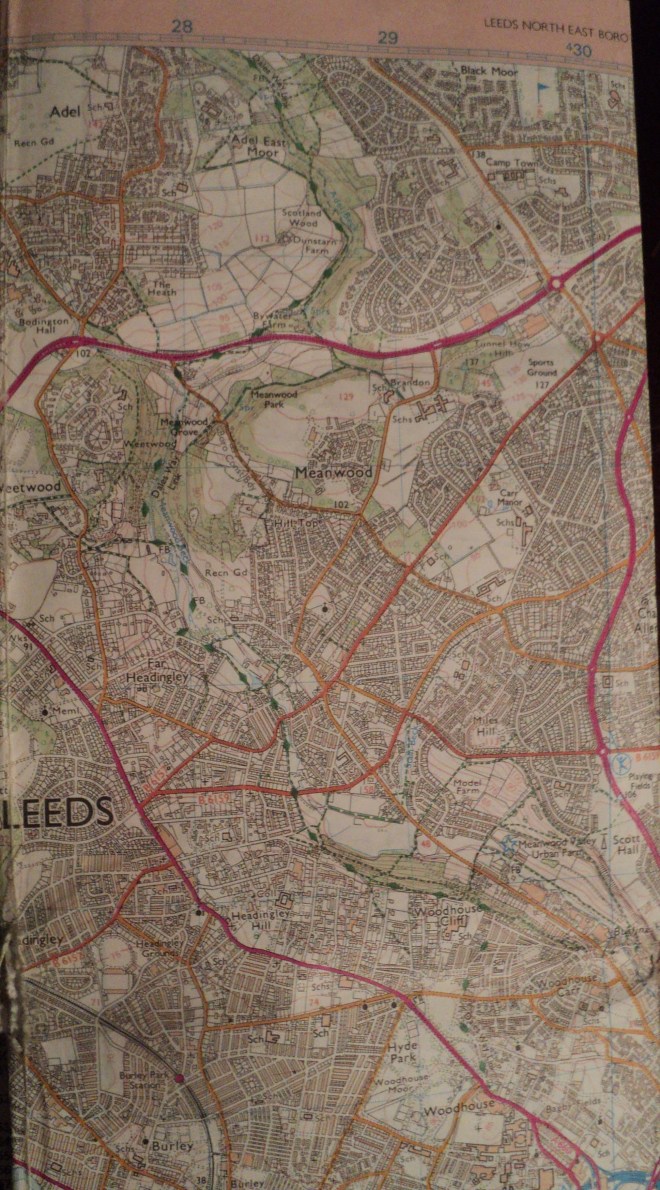

I ended up thinking about my first impressions of Meanwood Valley, which I got to know pretty well shortly after I moved to the area in 2005 (I’d never lived in Leeds before then). These days when people move to a new area, I guess they do some web searches and find out as much as they can about it online. But back then, and as a Rambler at heart, my first thoughts turned to the good old Ordnance Survey map.

And glancing at the map, the appeal of the Meanwood Valley to me was immediately obvious. Here was a green corridor extending almost from Leeds city centre, continuing for several miles north through the suburbs and out into the open countryside. Not only that, a clear public footpath ran all the way up the valley and beyond. Looking more closely revealed the words “Dales Way link” – thus Meanwood was a route by which you could walk from Leeds to the Yorkshire Dales and beyond.

Nowhere else in Leeds is this characteristic so marked. I suppose I was spoilt by having lived in Sheffield for many years where a number of green, accessible-on-foot valleys link the inner city with the Peak District to the west. So from the outset, I rather cherished the idea of one day walking out of my new house in Meanwood and (apart from the first 10 minutes of suburbia) all the way through countryside up the Valley and into the Dales.

But for one reason or another, for the next 8 years it never happened. And if it was easy to point to having young children to bring up as why, then this became the reason why it eventually did happen. Young child 1 had grown to become a restless 9 year-old with another long summer day to kill. “Why don’t we go for a walk or something Dad?” “OK, would you walk to Bramhope?” “Where’s Bramhope?” “Don’t worry, just follow me”.

We walked the 5 miles to Bramhope up the Valley, past Eccup Reservoir and into the village by some ridiculously-sized mansions. Then we got the bus back. 9 year-old had got the bug. Over the rest of that summer and autumn, we did a sequence of walks, each time driving to where the previous leg had finished, walking a few more miles, then getting the bus or train back. Bramhope to Menston, Menston to Ilkley, Ilkley to Bolton Abbey, Bolton Abbey to Grassington and, finally, Grassington to Buckden. We’d gone from Meanwood to the top of Wharfedale in 6 steps – 40 miles or so in total. For 9 year-old (now 12) it was quite an achievement.

Buckden is the bus terminus, so our journey was forced to stop there. But still there was something magical about the adventure, about having had the chance to escape from the city and into the National Park on foot. I’d like to think that future newcomers to Leeds would have the same chance.

Otley Chevin from Burley Moor

Approaching Bolton Abbey

Burnsall bridge

Crossing the Wharfe near Hebden