I was asked the other day why I thought the Meanwood Valley was so special. As I’ve spent much of 2016 trying to help protect one particularly valuable corner of the Valley, I thought this was a pretty timely question.

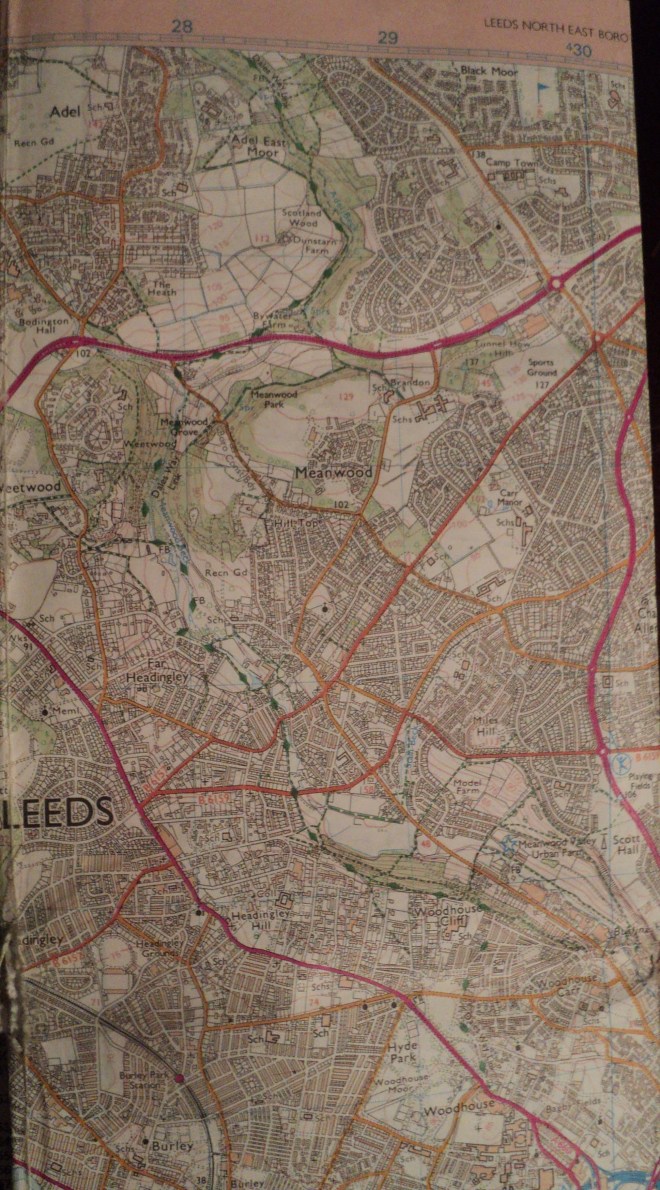

I ended up thinking about my first impressions of Meanwood Valley, which I got to know pretty well shortly after I moved to the area in 2005 (I’d never lived in Leeds before then). These days when people move to a new area, I guess they do some web searches and find out as much as they can about it online. But back then, and as a Rambler at heart, my first thoughts turned to the good old Ordnance Survey map.

And glancing at the map, the appeal of the Meanwood Valley to me was immediately obvious. Here was a green corridor extending almost from Leeds city centre, continuing for several miles north through the suburbs and out into the open countryside. Not only that, a clear public footpath ran all the way up the valley and beyond. Looking more closely revealed the words “Dales Way link” – thus Meanwood was a route by which you could walk from Leeds to the Yorkshire Dales and beyond.

Nowhere else in Leeds is this characteristic so marked. I suppose I was spoilt by having lived in Sheffield for many years where a number of green, accessible-on-foot valleys link the inner city with the Peak District to the west. So from the outset, I rather cherished the idea of one day walking out of my new house in Meanwood and (apart from the first 10 minutes of suburbia) all the way through countryside up the Valley and into the Dales.

But for one reason or another, for the next 8 years it never happened. And if it was easy to point to having young children to bring up as why, then this became the reason why it eventually did happen. Young child 1 had grown to become a restless 9 year-old with another long summer day to kill. “Why don’t we go for a walk or something Dad?” “OK, would you walk to Bramhope?” “Where’s Bramhope?” “Don’t worry, just follow me”.

We walked the 5 miles to Bramhope up the Valley, past Eccup Reservoir and into the village by some ridiculously-sized mansions. Then we got the bus back. 9 year-old had got the bug. Over the rest of that summer and autumn, we did a sequence of walks, each time driving to where the previous leg had finished, walking a few more miles, then getting the bus or train back. Bramhope to Menston, Menston to Ilkley, Ilkley to Bolton Abbey, Bolton Abbey to Grassington and, finally, Grassington to Buckden. We’d gone from Meanwood to the top of Wharfedale in 6 steps – 40 miles or so in total. For 9 year-old (now 12) it was quite an achievement.

Buckden is the bus terminus, so our journey was forced to stop there. But still there was something magical about the adventure, about having had the chance to escape from the city and into the National Park on foot. I’d like to think that future newcomers to Leeds would have the same chance.

Otley Chevin from Burley Moor

Approaching Bolton Abbey

Burnsall bridge

Crossing the Wharfe near Hebden