I recently blogged about my experiences of a long-weekend tour of 3 classic fell races – Burnsall, Grasmere and Kilnsey. To follow this up, I wanted to make some observations about something I have zero personal experience of, namely the record-breaking, elite end of fellrunning.

Take a look at the current records for these 3 famous races, plus a fourth, the Ben Nevis race, which always takes place at the end of the same week:

| RACE | FEMALE | MALE | ||||

| Record-holder | Year | Time | Record-holder | Year | Time | |

| Burnsall | Victoria Wilkinson | 2018 | 15.58 | John Wild | 1983 | 12.48 |

| Grasmere | Victoria Wilkinson | 2017 | 15.05 | Fred Reeves* | 1978 | 12.21 |

| Kilnsey | Victoria Wilkinson | 2017 | 9.39 | Mick Hawkins | 1982 | 7.35 |

| Ben Nevis | Victoria Wilkinson | 2018 | 1.43.01 | Kenny Stuart** | 1984 | 1.25.34 |

* Kenny Stuart ran 12.01 over the same course in a separate race in 1985

** John Wild ran Ben Nevis 1 second slower – 1.25.35 – in 1983

Two obvious things stand out from the table. Firstly, Victoria’s performances over the last year or two have been pretty extraordinary, and many congratulations to her. She is giving the strong impression of being a “once in a generation” athlete, with a couple of the records (Burnsall and Ben Nevis) having previously dated to the 1980s. It’s a great privilege to stand on the same start line as her (before seeing her disappear rapidly into the distance).

By comparison, the Male records remain stuck in that whole previous era of fellrunning. Why is that? Is it because there just hasn’t been a male “Vic” in the intervening period? Or are fellrunners generally not as focused on these races as once before? Or was there something in the water in the late ’70s/early ’80s? Or something else?

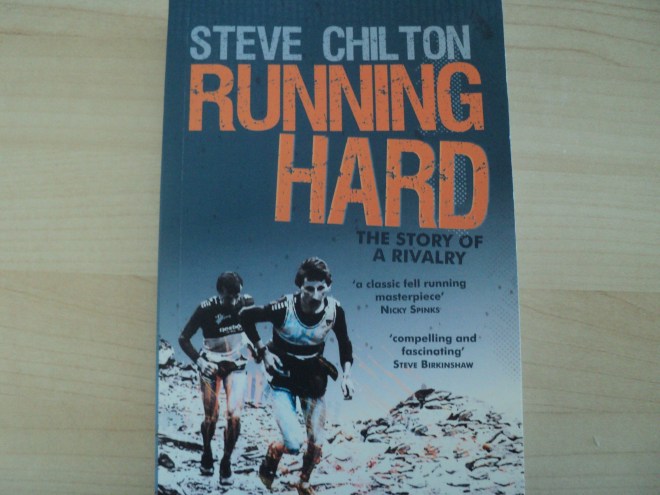

Fortunately (as many will already know), there’s a good book to hand that takes an in-depth look at the top-end of male fellrunning in this period. Steve Chilton’s “Running Hard – the story of a rivalry” focuses on the intense (but friendly) competition between John Wild and Kenny Stuart in the 1983 season. The names Wild and Stuart feature strongly in my table above. The strong implication reading the book is that there was something special about that period, and that perhaps we shouldn’t be surprised that so many records date from it. A combination of exceptional athletes, bringing the best out of each other, in a focused race timetable. I also referred to the daredevil descents in my previous blog, and Wild – a former Commonwealth Games steeplechaser – reveals that he hurdled the famous wall at Burnsall. Mind boggling!

No doubt the 1983 fellrunning season passed most people by at the time, so over the last year or so it’s been great to see “Running Hard” on the shelves of bookstores and libraries. It’s certainly a tale worth telling, and like Steve’s previous books, it’s one all fellrunners will want to read. Get hold of a copy here

The importance of “friendly rivalry” is emphasised by the well-known story behind one of the other records in the table, Fred Reeves’ Grasmere record. Prior to his 1978 time was a decade of incremental improvements by himself and his friend/rival Tommy Sedgwick. Indeed, the quote attributed to Fred – “It’s not my record, it’s our record” remains my favourite sporting quote, demonstrating as it does the gratitude we should show to our close rivals for bringing the best out of us, rather than any bitterness or resentment. Which only makes Victoria’s recent exploits seem the more remarkable, as she’s set her records without an obvious rival pushing her all the way.

The importance of “friendly rivalry” is emphasised by the well-known story behind one of the other records in the table, Fred Reeves’ Grasmere record. Prior to his 1978 time was a decade of incremental improvements by himself and his friend/rival Tommy Sedgwick. Indeed, the quote attributed to Fred – “It’s not my record, it’s our record” remains my favourite sporting quote, demonstrating as it does the gratitude we should show to our close rivals for bringing the best out of us, rather than any bitterness or resentment. Which only makes Victoria’s recent exploits seem the more remarkable, as she’s set her records without an obvious rival pushing her all the way.

Meanwhile, as they say, “records are made to be broken”, and – following Victoria’s example – it would be great to see some of the male records go the same way in the next few years. I’ll still be just coming round the cairn as you guys cross the line, of course….

Turning left on a side road, an additional 5-mile drive brings you to the car park at the foot of the mountain (note there’s only room for about 10 cars so on busy days you might want to try and arrive early). From here you get a better impression of the challenge ahead:

Turning left on a side road, an additional 5-mile drive brings you to the car park at the foot of the mountain (note there’s only room for about 10 cars so on busy days you might want to try and arrive early). From here you get a better impression of the challenge ahead:  The first objective is the low point on the ridge, about three quarters along to the right. In days gone by, you took a beeline to it from the car park, but heavy erosion of the path (on a mountain that nature is rapidly eroding anyway) led to the construction of a sensible alternative. So now, the path circuits the mountain, and you arrive on the ridge from the rear. I chose to travel anti-clockwise, ie climbing to the right of the photo. (Later – while it was satisfying to complete the circuit – I found the descent route to be pretty boggy by comparison; thus you might consider climbing and returning on the same, drier, route).

The first objective is the low point on the ridge, about three quarters along to the right. In days gone by, you took a beeline to it from the car park, but heavy erosion of the path (on a mountain that nature is rapidly eroding anyway) led to the construction of a sensible alternative. So now, the path circuits the mountain, and you arrive on the ridge from the rear. I chose to travel anti-clockwise, ie climbing to the right of the photo. (Later – while it was satisfying to complete the circuit – I found the descent route to be pretty boggy by comparison; thus you might consider climbing and returning on the same, drier, route). Braver souls may consider a traverse west along the ridge. Well, the reward is increasingly improbable outcrops of sandstone, sculpted into precariously-balanced pillars, and increasingly sensational situations, with severe levels of exposure:

Braver souls may consider a traverse west along the ridge. Well, the reward is increasingly improbable outcrops of sandstone, sculpted into precariously-balanced pillars, and increasingly sensational situations, with severe levels of exposure:

The flip side is that at several points progress is impossible without a very good head for heights, and the ability to climb and circumvent various rocky obstacles. Having managed to scramble up a steep gully, and then skirt an awkward jutting-out rock, I baulked at “the crux” of the ridge – a 10ft rock tower with a sheer drop of 2000ft on either side. That would have been a step too far for me.

The flip side is that at several points progress is impossible without a very good head for heights, and the ability to climb and circumvent various rocky obstacles. Having managed to scramble up a steep gully, and then skirt an awkward jutting-out rock, I baulked at “the crux” of the ridge – a 10ft rock tower with a sheer drop of 2000ft on either side. That would have been a step too far for me.